Musicians of all ages can fall into a bad habit of just learning their part. Anyone can learn their part for the next band concert, their solo for the next orchestra concert, or their technical passages in their chamber ensemble, but learning an individual part is only one piece of the puzzle. Yes, it is the job of the conductor to keep all of the individual parts organized, but how much more could be achieved merely by increasing individual awareness? Have you ever had a chamber piece crash and burn, and your group just didn’t know what happened? Awareness and preparation are the answers.

The key element to this discussion is context. The word context refers to an autonomous whole, but the word content refers to smaller parts. According to Webster, the two definitions of context are:

1. The parts of a discourse that surround a word or passage and can throw light on its meaning.

2. The interrelated conditions in which something exists or occurs.

Below are a couple of examples of how important context is:

The key element to this discussion is context. The word context refers to an autonomous whole, but the word content refers to smaller parts. According to Webster, the two definitions of context are:

1. The parts of a discourse that surround a word or passage and can throw light on its meaning.

2. The interrelated conditions in which something exists or occurs.

Below are a couple of examples of how important context is:

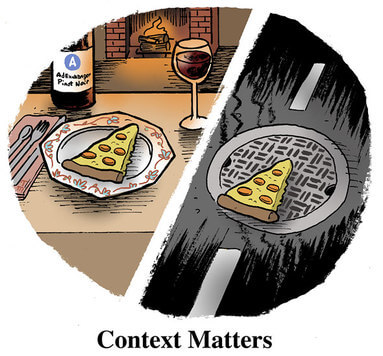

Context is more powerful than you might think. The pizza slice above takes on a whole new identity based on its environment. It’s not so appealing when it is lying on a sewer drain! Similarly, that excerpt you are practicing over and over again for your next audition is much more appealing in its intended context as well.

It’s amazing how a simple thought can change depending upon the… context! We expect our pets to curl up and take a nap in odd places but not airline pilots! Consider this the next time you find your cat napping in the fruit bowl or your dog asleep behind the sofa.

For a musician, there are two key ideas here:

1. The varying parts of a composition are interrelated!

2. Someone else’s part can shed light on what you are doing!

Sometimes the difficulty in music has nothing to do with the notes and the fingerings; it has much more to do with how you treat them, and the relationship that you create between your part and the larger ensemble. For example, expressive playing is a beautiful skill within reason—and within the boundaries of the composer’s work. Some liberties are acceptable and some liberties are expressive, but there are other liberties that are considered overboard, gaudy, ineffective, or inappropriate.

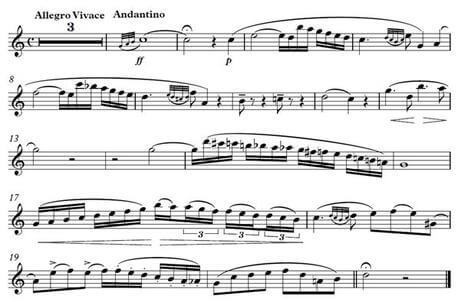

There are innumerable examples of how the context of an excerpt changes the performance of it, but the Overture to Rossini’s La Scala di Seta is a perfect example to point out. The oboe part below was excerpted directly from the orchestral score and includes all of the dynamic and articulation markings in the score.

For a musician, there are two key ideas here:

1. The varying parts of a composition are interrelated!

2. Someone else’s part can shed light on what you are doing!

Sometimes the difficulty in music has nothing to do with the notes and the fingerings; it has much more to do with how you treat them, and the relationship that you create between your part and the larger ensemble. For example, expressive playing is a beautiful skill within reason—and within the boundaries of the composer’s work. Some liberties are acceptable and some liberties are expressive, but there are other liberties that are considered overboard, gaudy, ineffective, or inappropriate.

There are innumerable examples of how the context of an excerpt changes the performance of it, but the Overture to Rossini’s La Scala di Seta is a perfect example to point out. The oboe part below was excerpted directly from the orchestral score and includes all of the dynamic and articulation markings in the score.

There are some liberties that can be taken with changing slurs and dynamics that would be encouraged, but there is a strong tendency to take liberties with the rhythms and the tempo that can get an oboe player in trouble with the orchestra. Some people see that they have a lyrical solo, and they get a little too excited. In a prominent solo like La Scala, other people have to be able to play with you, phrase with you, arrive at cadences with you, and join you in the affect that you are trying to achieve! There are expressive tools that can enhance this experience, but there are also expressive tools that can undermine your intentions.

The bottom line is: Don’t play like you are in a vacuum! Be expressive and play beautifully, but make informed decisions about phrasing!

The bottom line is: Don’t play like you are in a vacuum! Be expressive and play beautifully, but make informed decisions about phrasing!