Category: Teaching

What Kind of Teacher are You? Part Two

“The constructs of those participating frame all conversations, all acts of teaching. As teachers we cannot, do not, transmit information directly; rather, we perform the teaching act when we help others negotiate passages between their constructs and ours, between ours and others… teaching is an interactive process with learning a by-product of that interaction” (Doll, p. 271, 2009).

As an oboe teacher, I can not expect my students to understand and apply a concept through a simple statement or explanation. How can that be expected from them? What seems like a basic idea usually consists of a complex set if ideas. Asking a student to play more “musically” is one example of a simple request that requires something more. It places a demand on the student to understand what I think it means to play musically and what tools or skills they have to help them achieve it. The act of teaching is not to say, “play more musically,” but to teach them how to think about playing music–both understanding what you mean and what they prefer.

Going back to the metaphor from Part 1, the dinner party host does something similar. They can’t teleport food from their oven to their guests’ stomach. It doesn’t work that way. There are a lot more steps involved. The host has to have something to feed them like the teacher has to have some knowledge to share. The host sets the table/serves the food like the teacher demonstrates concepts or knowledge. Then, the guests finally eat what their host has prepared, which can be thought of as the student playing an assigned etude or exercise. Contextualization makes the meal more meaningful–the details and the preparation. The same is true in a music lesson. Creating a new context for an etude or exercise makes it more meaningful to the student and helps them navigate those passages between their constructs and those of their teacher.

The host prepares by shopping for ingredients, and they schedule the event around the needs of the student or travel restrictions such as winter weather or rush hour traffic. A good host does not put their guest in peril or make them sit in traffic for at least an hour to get to the other side of the city. The host also has to consider their accommodations and know that the people they have invited will be comfortable in the space they will be in. The situation is as important as the meal. The meal could be the best in the history of mankind, but if the conditions are not conducive to a positive experience, then it is a fruitless endeavor.

Like the preparations for a dinner party, another aspect of this conversation is planning ways for students to “negotiate” those passages. Good teaching doesn’t happen by accident and neither does a great dinner party. The host plans a menu based on the tastes and needs of their guests, and they probably won’t attempt a new recipe for the first time. They also won’t serve spoiled food or something that they know their guest can’t eat or won’t enjoy. The dishes selected are probably tried and true and are appropriate for the guest. In private teaching, menu selection translates into appropriate exercises and repertoire that will interest and engage the student without frustrating or boring them.

There are two huge problems in the realm of private teaching: Giving students spoiled food (knowledge) and unappetizing dishes (repertoire). The second problem is easier to fix than the first. Either present the material in a way that makes it more relevant or choose something different! A bigger problem is the number of teachers that don’t know how or what to teach.

There are many great players who struggle to articulate how they can do what they do so well. Some teachers feed students exercises that are sour or repertoire that is too difficult, and they lose sight of teaching their students to grow based on the music they have consumed.

The dinner party metaphor is an ideal aim, but it isn’t always an option for the private instructor. When the stars align, the metaphor of a dinner party is a reality and both teacher and student have rewarding experiences. When either side comes to the dinner table unprepared or with different expectations, the student-teacher relationship is reduced to that of a patient and a dentist traversing the pain of a root canal together. The real question is how do private teachers resolve the differences between memorable experience and “pulling” focus and creativity out of their students like a dental procedure. Part 2 of this series will leave us with one question to consider: What can private teachers do pedagogically to increase their effectiveness inside and outside of their students’ lessons?

Doll Jr., W. E. (2009). The four r’s–An alternative to the tyler rationale. In D. J. Flinders & S. J. Thornton (Eds.), The curriculum studies reader (pp. 267-274). New York, NY: Routledge.

Julie C

Did You Just Say Oboe Camp?

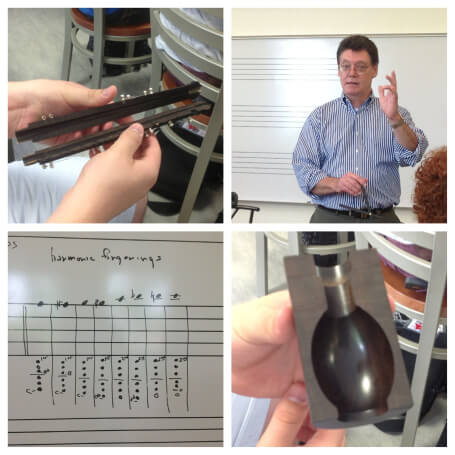

So what is oboe camp and why should your student go to oboe camp? Those are both great questions! Many students go to some form of camp during the summer, but oboe camp stands apart from any other type of camp. Midwest Oboe Camp is geared towards students of all ages and experience levels. The only requirement is one year of study in the oboe through school music programs or private instruction. Oboe camp is a unique experience for young oboists to be immersed in all aspects of the oboe including performance, private instruction, maintenance and repair, reed-making, chamber music, and technique specific to the oboe.

The Midwest Oboe Camp faculty includes Camp Director Julie Grasso as well as Professors Robert Sorton, Bailey Sorton, and Lisa Sayre. Midwest Oboe Camp Director, Julie Grasso, is a Yamaha Performing Artist and has been performing and teaching as a professional oboist for twenty five years. She is a founding member of a reed business, Double or Nothing Reeds, as well as a double reed quartet, Double or Nothing Ensemble, in residence at Xavier University in Cincinnati, OH.

Also a founding member of OBOHIO, Bailey Sorton has performed extensively in North America and Europe. Mrs. Sorton is an active educator in Ohio, teaching applied oboe at Kenyon College and Mount Vernon Nazarene University. At Kenyon, she also teaches bassoon and recorder and coaches the woodwind chamber ensembles.

Lisa Sayre is Adjunct Professor of Oboe at Reinhardt University as well as the University of West Georgia. Lisa was a member of the U.S. Air Force Band of Flight and is also a founding member of the Oxford Oboes Camp in Georgia.

Campers have the opportunity to work with our renowned teachers in masterclasses, lessons, and rehearsals, but they also develop critical-thinking, problem-solving, and leadership skills through performances and chamber music rehearsals. Students are divided into trios and quartets and given the opportunity to pick music and rehearse for a student chamber recital.

Campers spend two hours daily preparing a variety of trios for three oboes or for two oboes and English horn, but they also have an opportunity to play in a large double reed ensemble with both oboes and English horns. On the final morning of camp, students give a recital for the faculty and parents. The program includes the small chamber music ensembles as well as a large ensemble performance. For this year’s culminating recital, our campers, along with their counselors, performed Doug Harville’s arrangement of the first movement from Dvorak’s New World Symphony followed by New York Girls by Charles Sayre.

deeper understanding of reed-making.

Julie C

What Kind of Teacher are You?

A challenge issued by former CCM Music Education Professor, Dr. Liz Wing:

“The images that we hold as teachers influence not only how we see ourselves and our roles but how we frame the classroom environment, treat students and subject matter, and how students, in turn view us and themselves. The implications of these images permeate our daily lives and have the potential to affect profoundly the academic and personal growth of our students.”

Dr. Wing’s challenge is specifically for classroom music educators, but it is equally appropriate for anyone who interacts with students in a one-to-one or private studio setting. There is always a possibility for broader implications, but we are going to focus on the private music teacher for a few minutes.

Take a minute and think about yourself as a teacher. What does it feel like to work with students? What is your attitude and behavior like, and how do they change based on the situation? What metaphor or metaphors seem most appropriate for you? Here are a few examples to get you rolling:

- Air traffic controller

- Gardener

- Paramedic

- Bird watcher

- Judge & jury

- Circus master

- Traffic cop

- Coach

- Counselor

- Mother hen

- Drill instructor

- Pinch hitter

- Out in left field

- Diva

Some of these metaphors are more of an idealistic and others are more of an unfortunate reality. If we are brutally honest with ourselves, we have probably experienced more than one of these metaphors at some point in our teaching. Maybe it was strategic, or maybe it was an accident. Either way, awareness is the key.

Let’s pick an ideal scenario and delve into it. Let’s compare the private teacher to a host who is inviting a student (or a friend) to dinner. The educator as the dinner host is involved in fervent planning, shopping, cleaning, and organizing. The host has to considering dietary restrictions, organize the time to prepare the food, and have back up plans ready in the event of a surprise power outage or some other unforeseen obstacle.

This is a challenge I’m prepared to accept only as a metaphor and not as a reality. I won’t be inviting anyone over for a dinner party any time soon, but a dinner that goes off without a hitch is a carefully and methodically planned and organized series of events. Rarely, is it the result of a whim or spontaneity; even acting on a whim requires some sort of preparation. How is teaching a student any different? There is a certain level of preparation and planning that is imperative. The host prepares by shopping for ingredients—you can’t invite someone over for dinner if you have nothing to cook. This preparation and planning is paralleled in private music instruction. Being able to wiggle your fingers quickly does not mean that you are prepared to teach someone else effectively any more than knowing how to boil water or use the oven provides enough evidence that someone is ready to host a nice dinner. A host can’t cook with equipment that they don’t have or with skills that they have not acquired. It does not require great skill to put something on the table, but more skill is required to serve something that is enjoyable and suited to the tastes of the guests. Producing something memorable, rewarding, satisfactory, enjoyable, or meaningful requires something more in both cooking and in teaching.

Take a minute today to consider how you perceive yourself as a teacher and how you think your students perceive you as a teacher. We will be back soon with Part 2 and more ideas on the teacher as a dinner party host.

Julie C